The Buccaneers open with a little trick we saw San Francisco try a few weeks ago. Josh Freeman appears to be under center in a two tight end set. Freeman then stands up and moves back into the shotgun as one of the tight ends moves out wide to create a shotgun, three-receiver set, totally changing things for the defense. The two tight ends are Kellen Winslow and Jerramy Stevens, both of whom have been thought of as top-end receivers at certain points, though probably not now (definitely in the case of Stevens). They are the focus of this play.

It is Stevens who splits far out to the right with Winslow staying on the offensive line, though now standing up. Stevens runs a little out route to the sideline. Winslow comes behind him with kind of a smash route. I say ‘kind of’ because, though he is out of the view of the camera when he makes his move, it looks like Winslow doesn’t have a hard cut when he heads to the outside but rather is running up the field and towards an open area. That area is behind the corner, who goes with Stevens, but in front of the safety. The announcer, Tim Ryan, says the Packers are in Cover-Two, and if so, the area Winslow’s in is certainly a weak spot in the coverage.

AJ Hawk does stick with Winslow pretty much from the snap, but he just can’t stay with him as Winslow runs down the field, especially when Winslow has as much room to the outside as he does. Really, the only hope this play has from my estimation is if the safety comes up and takes away the outside, leaving Hawk to the inside. The safety, however, is also chasing Winslow from Hawk’s side. So Winslow is free to go out and catch the ball. The catch is a fairly impressive one, though it did not need to be. Freeman’s pass was pretty off-target though Freeman had no real obstacles: no pass rushers in his face, no defenders underneath Winslow and no cover men blanketing him. This was pretty much playing catch, or as close to it as you get in a game situation, and Freeman was just accurate enough and no more than that. This was a theme.

The next play was from the same formation as the ont eh Bucs motioned to: two receivers left, Winslow standing just to the right of the offensive line and Stevens out wide right. The leftmost receiver, Sammie Stroughter, motions to the right and takes off on a drag in that direction at the snap. The slot receiver in the left is running a ‘go.’ Winslow does the same from his position on the right. Stevens, meanwhile, runs your standard curl route, running upfield just long enough until the corner turns his hips, then turns back to the quarterback with a good bit of cushion.

Before we get to the pass, though, a word on the protection: the Packers rush five, and while no rushers get free, they do push the pocket. Cadillac Williams, it should be noted, does a really nifty job of picking up a blitzing defensive back. But everyone else is occupying rushers, but getting pushed.

Freeman does a beautiful job of moving in the pocket, running up and to the right to entirely remove the pressure. Moves like that are something to build on. Give me the list of the quarterback best at navigating the pass rush, and you’ll have the list of the best quarterbacks in the league. Not that this skill is the most important to being an elite quarterback, but it’s something all of the elite quarterbacks have.

Going back to the pass itself, Freeman wrecks all his good work by using his time to throw the ball across his body on the move to Winslow. The throw is behind Winslow and picked off by AJ Hawk. Had Freeman led Winslow more, Woodson was there and though he probably would not have picked off the pass, he would have had a very good shot at breaking it up. It’s a bad throw and a bad read. Hawk is penalized on the play, erasing the change of possession, but it’s for contact on the play before Freeman has made the pass. The correctness of the decision is not affected.

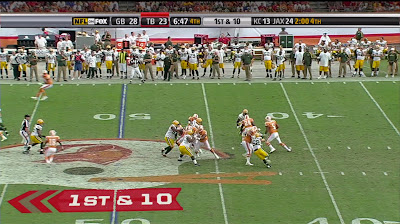

What is more condemnable about the throw to Winslow is how open Stevens is next to him. Look at the screen shot above that was illustrating Freeman's movement in the pocket. Now look at Stevens along the right sideline and how much space he has. There is one safety deep, so deep that he is there to clean up anything bad but not prevent it. As was the case with most plays on the drive, the Packers employed four linebackers, four defensive backs and just two down lineman. Covering the two threats to the right are two of the linebackers, a cornerback and another defensive over the slot. One of the linebackers and the extra defensive back blitz. That leaves the two receivers covered one-on-one. When Winslow’s quest for open field takes him a little bit across the field, he does pick up some coverage from Woodson in the other slot. With that situation, looking to the right side of the formation is a good decision by Freeman. However, he chose the wrong man. Hawk did a masterful job making up for the previous play, sticking with Winslow so well it was illegal. Stevens, meanwhile, is wide open on the curl and would have been ready to reel in whatever only-kind-of-on-target pass that Freeman decided to throw. It’s kind of cheap (but not so cheap that I won’t do it from time to time) to say ‘But so-and-so was open’ whenever there’s an incompletion. Quarterbacks have reads and limited time to get through them. If he is executing the play properly, he’s going though those reads, and if he doesn’t get to Stevens before he runs out of time, then so be it. But whatever. Winslow was not open, and Stevens was. I’m just saying.

The next play is the first example of the bunch formation we see a few more times on this drive. The bunch is three receivers, this time to the left, with the middle receiver on the line and the other two on either side of him, slightly off the line. They form a nice little triangle.

Kellen Winslow has his hand on the ground on the other side. The Packers again are blitzing on this play, again from the right side, so they leave their defense looking pretty balanced before the snap, with only three guys (an OLB on the line, Charles Woodson on the inside and Al Harris on the outside) guarding the receivers in the bunch. Then the OLB is shading pretty far to the inside. I guess this is to guard against any of the receivers who take routes over the middle. No receivers go over the middle on this play. At the snap, Michael Clayton and Maurice Stovall (Go Irish!), the two leftmost receivers of the bunch, head straight downfield to block. Sammie Stroughter drifts out behind them to catch a wide receiver screen of sorts. With the blitz from the other side and the Green Bay defense’s decision to devote a certain amount of focus to the middle of the field, the receivers are one-on-one against defensive backs. This play has a lot of potential, but Stroughter makes a mistake picking his blocks. Clayton does a great job walling off Woodson to give Sammie a lane to the outside, but Stroughter goes inside. On the broadcast, Ryan chides this as a bad decision by Stroughter. Watching the play several times, I think Stroughter actually lost his footing making a juke before cutting outside. Either way, Stroughter makes a mistake here and is not able to take advantage of the blocking downfield, which would have given the Bucs 10 yards at least.

The Buccaneers open the next play again in shotgun. Jerramy Stevens has his hand down on the right side of the offensive line, Kellen Winslow, Jr. is in the slot to the right with Michael Clayton on the far right. Maurice Stovall is by himself split wide to the left. Stevens runs deep while the two other receivers to the right run what I believe the professionals call a “levels” route combination: they both run square-in’s at different depth levels, hence the name (Here is a really awesome breakdown of the levels play: link). Or at least they try to run that. Stevens gets tangled up with Winslow, who falls down. There’s no way anyone could even know that, but I think it’s Stevens’ fault for drifting over when heading upfield. If anything, he could have cheated to the other side. Either way, the throw is to the other side of the field, to Stovall. The Packers’ are again playing with the one deep safety, who goes with Stevens. The OLB to the left is blitzing (which can be expected. Since they only have the two lineman, surely someone else is rushing.), and the inside linebacker to that side is playing sufficiently inside that Stovall is one-on-one with Al Harris.

Stovall takes advantage of the coverage to get open on a comeback route, which is similar to a curl in that you want to get the corner into his backpedal and then use that commitment by the corner to get open, but instead of just turning inside to the QB and sitting down as you do with a curl, you come back to the QB, moving towards the sideline and never really stopping as you sometimes do with a curl. On the comeback, the receiver has out the corner on the inside of the field and has a big gap to the outside and enough separation that the corner can't get to any throws placed between the wide receiver and the sideline near the receiver. This is the case with Stovall. He is pretty open and any ball between him and the sideline nets a very nice gain. Without any real pressure on him and only Al Harris, who has been beat, to worry about, Freeman throws the ball inside, where it is broken up. This is troubling. When you have this many things going right on a play (line protects well, receiver gets open, etc.), the quarterback has to be able to make a play like this. When I see something like this, where Freeman just misses open receivers, it makes me wonder how he got by at Kansas State. I guess college corners may have been so poor that he could throw it in the general vicinity of his receiver and that teammate could just go and get it, but it seems unlikely he could have had the consistent success usually enjoyed by a first-round pick with that sort of arrangement. That's the thing, though: Freeman had very limited success (read: none) at Kansas State and ended his career there with a completion percentage under 60%. This is the number one reason I do not feel confident about Freeman moving forward: you cannot have success without accuracy. I feel like it is the most important skill a quarterback can possess. Further, I'm not sure that inaccuracy like this can be fixed. I'm hard pressed to think of a quarterback who came into the league missing receivers and developed accuracy over time. It seems to me like on-base percentage in baseball: you're nearly born with it, and if you don't have it by the time you reach the pro's, you're not going to ever have it. If you can think of examples that go against this theory, please present them in the comments. It's certainly a theory I would like to submit to testing.

Next play, Tampa goes back to the bunch, on the right side this time with Michael Clayton alone wide to the left. The bunch does something that is irrelevant but interesting. The two receivers on the outside of the bunch—the two bottom points of the triangle—look at first like they’re running a pretty standard crossing pattern where they have routes that cross over each other, hopefully breeding confusion in the coverage as to who is guarding whom. But after two or three seconds the inside receiver, who has been going to the sideline, breaks the pattern up and back inside. The end result, best as I can tell, is that it looks like ‘levels’ again. To put it another way, they run a levels route set except the man taking the deeper square-in, the inside receiver, adds two or three steps to the sideline onto the beginning of his route. The results is the levels concept that is an easy read for the quarterback but very confusing for the defense, who can’t know what’s coming until 3 or 4 seconds into the play. But the ball does not go to them.

The middle receiver of the bunch runs a ‘Go,’ as does Clayton. Green Bay is playing with one safety over the top and a full seven players on the line (they rush six), though again only two have their hand on the ground. With only the one safety playing in the middle, Freeman has only to wait for the safety to commit to one of the two receivers running deep. The safety shades to the right, and Freeman throws it to Clayton on the left, who is one-on-one with Al Harris. It’s another throw that doesn’t land very close to the receiver, but in this case he looks like a savant. Harris is playing with a big cushion and never lets Clayton behind him. This is normally a very reasonable way to defend this route, but the throw is a little short and to the inside.

That gives Clayton room to come back and dive to the side to make a spectacular catch. In this case, had Freeman hit Clayton out in front of him or something more conventional than short and inside, then Harris may have had more of a play. As it is, he doesn’t really have a chance to react.

The next play is their second play of the drive from under center with two tight ends again to the open side, this time the left side. The two receivers are both on the right side. This play makes very little sense to me. With seven yards to go, Tampa goes to a max-protect pass with both tight ends in to block. The receivers then run your standard smash, curl combination. The inside receiver runs about 10 yards (a few less in this specific case) before breaking outside to his nearest sideline. It looks like the opposite of a post, if you’d like to visualize that way. Then the outside receiver runs a curl. It’s an effective route combo in a lot of situations, but I do not understand why it needs extra blocking. Extra blocking is something we need for complicated double-moves and deep long-developing routes, not something like this. And with only seven yards to go, one of those deep routes would be useless. I don’t know what benefit the Buccaneers get from having two fewer receivers on routes. I can tell you the cost is that their two downfield receivers are covered pretty easily by the multitude of defensive backs in coverage. The pass ends up going to Cadillac Williams running a swing pattern parallel to Freeman. This is another troubling throw by Freeman, since it is incomplete.

I again consulted with Bob who tells me throwing a swing pass is much harder than it looks, since there is quite a bit of emphasis on leading the receiver and you often have to loft it over whatever pass rushers in between receiver and quarterback who could put their hands up, which is a factor here. Still, NFL quarterback should be able to throw a swing pass, and Freeman tosses an incompletion here. Another factor in the play is Nick Barnett, who does an excellent job of diagnosing the play quickly and acting decisively, cutting into the backfield so that if Cadillac had caught the pass, it would have been for a loss. This was a play whose design was poor and ill-fitting to the situation that was further hampered by poor execution.

For their third down, the Buccaneers bring back their bunch, putting it to the right with wide receiver Brian Clark wide to the left. Freeman is again in the shotgun. The outside receiver in the bunch, Clayton, runs a ‘Go;’ Stevens, the middle receiver of the bunch, runs a square-in in the end zone; and Winslow, the inside receiver, runs an out and then cuts it upfield after a bit. There are three men (from inside out: AJ Hawk, Charles Woodson, and Tramon Williams) covering the bunch with a safety over the top of them. Hawk sticks close with Stevens on his square-in, Woodson picks up Clayton and sticks with him, taking away any sort of throw to the inside. Winslow is running counter to all of these, and despite being the inside receiver he is picked up by the outside defender, Tramon Williams.

Even once Williams decides to cover Winslow, he does so with a good bit of cushion. At pretty much every point on this play Winslow was open, and for much of it he was past the first down marker. Freeman does not target Winslow though, he goes for Clayton in the endzone, trying to throw it over Woodson to the taller Clayton.

It almost works, Clayton almost makes ana amazing catch in the back of the endzone, but he can’t hold onto the ball and may not have gotten his feet down in bounds anyways. It’s not a terrible idea to go for the six, and while the throw is high, it has to be to go over Woodson. My eyes say Winslow was a better idea, but this wasn’t a bad idea necessarily.

Tampa goes for it fourth down, operating from the shotgun with Winslow on the line with his hand on the ground, Clark is in the slot to the right and Sammie Stroughter is wide to the right. Michael Clayton is wide left. The ultimate result is that Sammie Stroughter beats his man for the touchdown. What interests me is two questions: how did he comes to be one-on-one and how did he beat that man?

As to the first query, the answer is in the routes of the other receivers. Clark runs an out from the slot, but his goal is not so much to run that out but rather to pick that underneath defender when he makes his turn to the sidelines. From the tight end spot, Winslow runs a post. The safety understandably commits to that, putting Winslow in double coverage (Woodson was on him from the snap) and taking both defenders into the middle of the field. So now there’s no safety over Stroughter, and any defenders covering other players that might be able to help once the pass is in the air are taken care of. With Stroughter single-covered, though, how does he work open?

The quick answer is a double move. Right past the first down marker, Stoughter slows up a few steps and turns his head as if he’s going to run a curl just past the sticks.

He’s never moving in an direction but downfield, but he gives the corner various false clues that cause that defender, Jarret Bush, to take two wrong steps out of his backpedal and forward towards Stroughter. Once Bush does that, he’s toast. Stroughter almost immediately puts his hand up to signal Freeman that he’s open, and Freeman does a nice job lofting the pass over Bush to allow Stroughter the catch in the back of the endzone.

Stroughter’s an interesting player. He had nearly 1,300 yards in his sophomore year in 2006, earning third-team All-American. Then in 2007, he took a leave of absence for most of the year, citing some personal troubles surrounding the deaths of two family members and one of the Oregon State coaches in separate incidents. He came back for his senior year of 2008 and again topped 1,000 yards, but the questions about makeup were enough to push him down to Tampa in the seventh round. That seems a little mystifying to me. Yes, it seems a little much to talk about quitting football, as he did in his junior year, but he came back from that to record another 1,000-yard season, certainly that makes enough of a indicator he was back. It’s not like he was mixed up with drugs or any of that, and I think he is proving now that teams made a mistake passing on him. He’s had some level of buzz around him since training camp and has seen that turn into a decent amount of playing time. He’s had at least one catch in every game this season, which is more than Darrius Heyward-Bey or Michael Crabtree can say (though I guess that’s kind of a cheap shot in Crabtree’s case). He's no guaranteed star or anything, but he's been very useful, and good for him.

It was interesting to see Green Bay running a 2-4-5 defense for the entire drive. From the standpoint of the Cowboys playing the Packers this week, it was also interesting to see the lack of pass rush despite some attempt to blitz. Save for the play erased by penalty where Freeman had to step up to avoid the rush, there wasn't a throw really affected by the pass rush. Many of the defenders in coverage represented themselves well, making a play at some point on the drive (Hawk intercepting Freeman, Harris breaking up the pass to Stovall, Woodson sticking with Clayton in the end zone, Barnett sniffing out the swing pass), and there were no plays with major defenisve breakdowns where someone just lost track of a receiver (except maybe the third down play in the red zone where Winslow was open, but in that case, Tramon Williams was at least aware of him, he just couldn't fight through the trash to cover him). Still, you have to think Miles Austin, Jason Witten, etc. will have time to work open. No defender can cover a receiver forever, and if Green Bay couldn't bring pressure against Tampa's line protecting a roookie quarterback in his first start, then the Cowboys' receivers may well have forever. Just thinking about it, the formation could have something to do with it. With so many cover men on the field, it makes sense that they would be staying with receivers but with only two lineman on the field, there's a lot of linebackers struggling against offensive tackles that are much bigger and stronger than these linebackers. The linebackers are generally likely to be more nimble and quick than the tackles, but that never turned into any sort of pressure. The tackles did awesome all though the drive.

A final word on Freeman: he's young, and one game is not enough to make a definitive statement on his entire career ahead of him. That said, that's what we do here: we try to make conclusions based on careful study of minutiae (or a sloppy look at insignificant details, based on your point of view, I guess). The biggest factor that said to me that he was or was not going to be an elite quarterback was the accuracy of his passes. His throws were consistently off-target. The times when a receiver was open and Freeman didn't see him, I feel those things can be improved both in film sessions by pointing it out to him that the receiver was open, and in practice where he gets a better feel for the plays and how to process the reads on those plays. Not seeing open receivers can be fixed. The poor throws, however, I just don't see how that gets better. If I know he's supposed to put the ball outside on a comeback route, he knows that. Coaches have probably told him that thousands of times by now. The fact is, after 10+ years of training, he doesn't know how to get that ball where it needs to go. That makes me think he never will. And the numbers support this. Football Outsiders' studies on college quarterback prospects strongly suggest accuracy is one of the two most important statistics in predicting success in the pro's: if you're not an accurate passer by the time you're done with college, you're probably not going to be one. And as far as determining accuracy goes, completion percentage is very helpful, but it doesn't tell the entire story. There are factors outside of accuracy (receivers dropping balls, poor protection forcing the quarterback to throw the ball away, etc.) that drive down completion percentage. So the fact he had a percentage below 60 in college is a bad sign, but not a definitive one. What he did on Sunday, struggling to place throws where they needed to be placed--when taken with the completion percentage in college--paints a more damning picture. I would, of course, love to be wrong about this: good quarterback play is awesome, I'm happy to have more of it. But I didn't think Freeman was the answer when people began to regard him as a potential first-round pick, and I saw nothing here that convinced me otherwise.

1 comment:

Dude, are you kidding me with this?

Post a Comment